Jogintė Bučinskaitė in conversation with with Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas about the tvvv.plotas, a project broadcasted on the LRT, national television channel (1999)

J.B. Looking back from today’s perspective, how do you recall that time and the tvvv.plotas project? Did it have any impact on your subsequent works?

G. U. That time served as the tipping point – values, cultural and social habits were changing, technologies were developing with lightning speed. Social networks — as we know them today — were nonexistent. At that time, tvvv.plotas helped us to understand the social dimension of art, its role in combining various spheres of life and its agency in creating the public space. tvvv.plotas helped us to further articulate the activities of Jutempus1 as the platform of experimental art research and also transfer those experiments from physical to media space. Subsequently, the projects Transaction2 and RAM6: Social Interaction and Collective Intelligence developed out of that line of thinking. It could be said that these projects were constructed as network models that were to shape a new community built on artistic dialectics in the conditions of capitalist contradictions.

N. U. tvvv.plotas impacted the topics we developed further. Since I filmed and edited a lot of material myself, the first thing that I found troublesome was that basically mostly men spoke in the television episodes we filmed. This inspired the quest for a feminine (and, later on, a protest) voice in our subsequent works and especially in the projects Transaction, Ruta Remake, and Pro-Test Lab.It was really interesting to reflect on the boundaries of television as a format. At that time, television was approached merely as a broadcasting channel without any feedback. We sought to expand communication and, therefore, supplemented TV broadcasts with physical gatherings in the premises of the Lithuanian Artists’ Association as well as with online conversations that had already been possible on the web. We wanted to expand the notion of public space as the means of communication; to reflect on it and probe all the new possibilities that were opening up with the technology of those days.

G. U. We got completely immersed in this project as if it was our future. We left the physical premises of Jutempus in the former Cultural House of the Railway Workers and experimented with an idea to carry out an artistic project in virtual communication or television space. The proposal for a cultural program at the national television station was a decoy — at least so we thought at that time — to implement our radical ideas in art and public sphere.

J. B. Could you tell us more about broadcasting circumstances and the episodes you’ve mentioned?

G. U. Ideally, we imagined moving the interdisciplinary research field of Jutempus to a digital realm, to television. It seemed to us like a teleportation experiment. Since television broadcasting is one-way, we had to develop that spatial feedback, considering meetings in physical space. We wanted those meetings to take place not in some representative location but rather in a marginalized one. Paradoxically, the Lithuanian Artists’ Association offered us a venue for meetings. We placed a television set there and invited everyone to watch episode together, as if it were a physical exhibition opening. When a contemporary art institution and its supervising Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) became a new establishment, artists needed to go underground (laughs). Such was our performative comment.

N. U. It is true that communication and its experimental form were of great importance! Each of the ten episodes had a flyer of exquisite design by Darius Čiuta that was sent by post to all loyal visitors of Jutempus exhibitions across the country as well as to addressees living abroad. In the TV episodes, we engaged interlocutors from various countries. By utilizing webcasts, we wanted to expand the media language, as well as a field of references, topics, values, and articulation. And it was all in 1999, in the times of a dial-up internet!

G. U. We had to connect to a server in Amsterdam to access the advanced webcast platform developed for the interaction of football fans in the Netherlands while watching World Cup matches. Media nerds and hackers had developed the required software. In addition, we used the software CU-SeeMe alongside the webcasts. In this software, you could chat and see your interlocutors in the form of their avatars. Internet bandwidth was very limited at that time, so the very fact that you could actually “see” your audience in real time was absolutely incredible.

N. U. I remember I used to chat with Paulina Eglė Pukytė.

G. U. Yes, Eglė Paulina and a handful of other emigrant Lithuanian artists never missed a broadcast. We had fans among a non-Lithuanian speaking audience too. More than half of the interviews were in English.

J. B. Is this how the TV program name came into being? Did you want to turn your television broadcasts into some kind of world wide web (www)? And if so, what does the word “plotas” refer to in the name?

G. U. It was a kind of puncept, a blend assembled from the word pun (a joke exploiting the different possible meanings of a word or the fact that there are words which sound alike but have different meanings) and a concept – an artistic concept and a joke at the same time. So yes, the reference to www is there too. We were interested in communication and discussion platforms organized earlier by artists themselves. For example, the magazine VVV edited by conceptualists and surrealists. For us, the word “plotas” meant the relocation from the physical to a discursive realm. As we were really interested in appropriation and subversive strategies at that time, we wanted to infiltrate national television and produce our space, our “plotas.” In other words, we wanted to hack the body controlled by various standards and regimes.

J. B. I’d like to ask you to go back in time and to remember how the very idea of the program as well as the collaboration with the public broadcaster (LRT) came into being.

G. U. The exhibition Lithuanian Art’97 / Galleries Present organized in 1997 at CAC must have served as the initial impetus. Various galleries such as Vartai, Langas, Arka, and others — including us with Jutempus — were invited to participate in the exhibition. Even though we stated that we were not a gallery and that we were only carrying out interdisciplinary art-based research projects, CAC director Kęstutis Kuizinas wanted non-commercial platforms to be present alongside commercial galleries. There on the first floor of CAC we tried to reconstruct the atmosphere of Jutempus deploying various artifacts of artists. We had a semi-legal bar installed, where artist Evaldas Jansas baked buns with hemp; the artists-brothers J & J Vaitekūnas organized a special presentation of the project “The Distillation” (including a limited edition of moonshine); artist Artūras Raila featured his landmark performance with bikers. Slide and video projections on the walls were filling the space of CAC with sounds and images of social interaction from the openings and exhibitions at Jutempus’ space. Instead of focusing on objects-artworks, we rather addressed relationality, focusing our attention on the milieu, the social environment, and artists themselves. We didn’t sell the artworks; we articulated the question of economy in a different way. We suggested that artists should acknowledge cultural and social capital and consider their clothing, for example. That is how the fashion collections of Evaldas Jansas, Donatas Jankauskas-Duonis, Patricija Jurkšaitytė, and other artists came into being and served as commentary on the art system itself, as well as on its attention economy. Soon, this commentary was featured in the fashion and lifestyle magazine Linija3 as an art performance by curator Raimundas Malašauskas. In this context of relational aesthetics and emerging art communities, we were approached by artist and TV producer Linas Augutis. Linas had television experience, thus he invited us to submit a joint application for a TV program on the LNK, the first independent commercial channel. The draft application had already included the name of Raimundas Malašauskas, who suggested the scenario where a curator would take the lead as a host presenting art phenomena, while artists would assist him by putting the ideas into shape. Well, we thought that the future show had to be a program organized by artists themselves; just as we organized various other projects at Jutempus. As a result, there was the difference in concepts and, consequently, our application for LNK was never even considered; something changed there or was canceled. Simultaneously, the LRT had just announced the tender for cultural programs with Viktoras Snarskis as a producer. Snarskis had already produced the TV show Style, a national success, with Violeta Baublienė. Our application won the tender. We simply played with the concept of a cultural show, having decided that we were not going to conventionally engage artworks but rather unfold the context that had shaped them, focusing on the articulation of what an artwork and the milieu that nurtured it actually were. We were interested in the constituent elements of such articulation; what social groups impacted the language of art — artists themselves, artists and relatives, artists and children, artists and institutions.4

The process of creating these television episodes was really compelling, like a machine learning instrument that is learning new concepts, new meanings, new vocabularies generates new audiences. We thought that television could actually help us sense that generative art process, communicate how ideas come into being. And ultimately, it was really important for us how those ideas were articulated — not only in Lithuania but also in other cultural contexts — how they escaped the gravitational forces of the center or the periphery. We wanted to discuss what was and what wasn’t the market, the institution, the mainstream trends, and the underground. That was how the entire spectrum of themes — from an intimate family environment to subcultures and so-called high art — emerged.

J. B. What were those technical working conditions at the television at that time? You included the fact in the captions that the program had been edited in a digital editing room. To my knowledge, the LRT did not have such an editing room at that time. It’s obvious that the technical side of the program was extremely important for you. To what extent and what sort of decisions were determined by those technological limitations?

G. U. Looking from the perspective of the television professionals, we (artists) came “from the street,” i.e., we hadn’t had any professional education in directing, video cameras, or TV journalism; thus, in the eyes of television producers, we were strangers. We didn’t have any basics in television (laughs). While the technical standard then was Betacam5, we acquired one of the first Sony MiniDV camcorders that recorded a digital signal onto a cassette. That camcorder was equipped with the FireWire serial bus (IEEE 1394), so the signal could be transferred directly to the video card on the computer, which eliminated the need to rerecord from tape to tape during editing. The first reaction of the LRT engineers was that the MiniDV format would not deliver the sufficient quality required for the broadcast. Meanwhile, the BBC equipped its journalists with the same MiniDV camcorders, challenging Betacam video standards, so the LRT finally agreed to accept our material.

N. U. Worth mentioning that our project was supported by the SRTV, the National Press, Radio and Television Support Fund, while the LRT gave us advertising slots and funds for digital editing. According to the agreement with LRT, the editing had to be done at Videopolis, a company included in the package.

G. U. The editing room of Videopolis was up to the standards of the time and equipped with new G3 Apple and Silicon Graphics computers. Vytautas, a truly talented editing director, taught us a lot. At the beginning, the Videopolis producers were horrified by our desire to bend standards, whereas we were totally engrossed in the entire process. We must have seemed like kids in a candy store. We confronted the meager television environment and media language of that time by bringing in certain insights of video art and experimental media. If television shows were made to be easy recognized and identified —from audio vignette, graphic style, font, video tab, host’s character — we mastered each episode radically differently. In the then discourse of developing Lithuanian brands, media, and communication, it stood out as an anti-brand. N. U. The idea of breaking through conventions was compelling to us. Just as we started to follow the advice of television producers and do things “correctly,” we felt we were losing authenticity. For example, the final episodes were more similar to what TV shows “should” look like. In reality, the project was taking all our time; however, insufficient funds and lack of basic things such as video cassettes was precarious. Today, this may seem strange, but then we didn’t have enough MiniDV tapes, so most of the video material hasn’t survived. Having rerecorded the video material in the master copy, we would later film on top of it. To save MiniDVs, we would rerecord the material for viewing on VHS. I can still recall myself spending early mornings fast forwarding and rewinding VHS cassettes and transcribing texts.

J. B. So, you filmed everything together, the two of you?

G. U. Nomeda filmed since she has the eye of a photographer.N. U. Linas Augutis also filmed. Linas and I filmed everything with one camcorder, interchanging, learning how to film. The knowledge I acquired as a student at the photo lab at Vilnius Academy of Arts came in really handy.

J. B. Who ran the photo laboratory at that time?

N. U. Diana Stomienė ran the lab at that time, with lab technicians Alvydas Lukys as her right hand and Gintautas Trimakas, perhaps as a left hand (smiling). However, activities they engaged students with weren’t obligatory. Perhaps time in the photo lab was the most interesting part of my studies. I developed a certain practical skillset, but that was far from enough for the craftsmanship needed to produce the TV program.

J. B. And how did the LRT respond to your first episodes of the program?

G. U. Their initial reaction was shock. Once we submitted the first episode for the signal quality check, the outraged engineer refused to broadcast, stating that we delivered total rubbish full of acoustic noise. The show producer and the editorial department were totally freaked out as the episode had to be aired soon. It took us a while to explain that soundtrack was not technically defective but rather a manifestation of cultural noise (laughs). The noises for the episodes were composed by architect and sound artist Darius Čiuta from Kaunas. Darius would send over a MiniDisc containing an audio recording by bus, and we would collect it in Vilnius and add the sound on top of the video in the editing room. It was like a blind date — they either corresponded, or not. And in that first tape, Darius included the frequencies that were mistakenly regarded as sonic defects by the LRT engineers. Thus, the term cultural noise spread among the technicians, making them true fans of the program for its technical puzzle. Darius Čiuta “made” the sounds for all the episodes, bearing that conceptual idea of a theme in his mind but not knowing anything about the moving image and the montage. We only discussed the themes, script, and narrative by phone. As a result, the sound did not illustrate the action but rather disrupted the image with its elements of glitch aesthetics, simultaneously generating a different, nonlinear dimension of the story. The first three episodes were aired at prime time, and got high TV ratings, even higher than those of the show Style. Perhaps we crossed the line because tvvv.plotas was moved to a later time. It was really compelling to know who our audience was. Once we met our Russian neighbour, and she told us, “Мне так понравилась ваша передача” (“I really appreciate your program.”). It was surprising to learn she was watching tvvv.plotas. We asked her, “А почему?” (“And why?”). She replied, “Ну как почему, мне же так интересно посмотреть, как думают молодые люди. Я даже смотрю повторение всегда” (“What do you mean ‘why?’ I’ve always been interested in how young people think. I also watch the repeats.”). The program was aired on Wednesdays and repeated on Saturdays. It was really unexpected and pleasing to learn that the program, of such experimental artistic language and form, cultivated diverse audience.

J. B. But before you started creating the program had you envisaged your target audience?

G. U. On the one hand, conceptually, we were interested in teleportation of the Jutempus physical space to televised space. On the other hand, tvvv.plotas sought to break the stereotype of what a conventional cultural show was supposed to be, with expectations to cover exhibition openings, inform the audience about events, or invite experts to interpret what has been represented. In other words, our project was aiming to escape representation, demonstration of artworks; rather focusing on research and context, on generating the milieu that nurtures the artworks. The question raised in this effort addressed the possibility of artistic research in television; whether with the help of a camcorder it would be possible to infiltrate, hack into, or reveal the formation process of artistic thinking and articulation. Of course, primarily, we were focusing on the local art public that participates in production of the cultural milieu; and considering the topics that, in our opinion, could speak to pressing urgencies of the time. In addition, we were interested in the idea of “art as communication” and what experimental media forms could be developed to engage diverse publics without succumbing to the mission of spreading cultural news.

J. B. If the program was rather popular, why were only ten episodes aired? Why didn’t you continue the project?

G. U. To be honest, I don’t remember our exact agreement with the LRT now. It is likely we agreed on twenty five episodes to be broadcasted in 1999–2000. Eventually we ended up with a pilot consisting of ten pieces aired in 1999.

N. U. It was rather challenging to produce a radically different half-hour-long episode every second week.

G. U. As artists, we weren’t planning to become a part of the television machinery. To us, art makes sense as a model (or a prototype) rather than a scaled-up solution or application.

N. U. Those episodes demanded quite a lot of resources; after six continuous months of interviews, videography, archival work, and editing we badly needed a break. I remember that during the editing of the final episodes I could hardly sit in the editing room. The production of the first episodes took way too much time.

G. U. Indeed, the editing of the first episode took us nearly fifty or sixty hours (laughs).N. U. And the last one – only four. Such was the progress (smiles).

J. B. You worked on the show together with Darius Čiuta, Linas Augutis, Robertas Kundrotas, Artūras Raila, and numerous other interlocutors from several countries. How was this team formed?

G. U. We started from designing a flyer with the map that traced potential themes. Inspired by Simon Patterson’s artwork The Great Bear that looks like the London Underground Tube map, we suggested lines as trajectories of thought and destinations as topics. The flyer included an open invitation to further suggest themes and take part in the interview sessions. It contained an email address where such proposals could be sent.

N. U. It was a kind of an open call.

G. U. That theme map-flyer was on public display at the CAC exhibition. It was also sent out to numerous institutions and individuals and distributed as a poster. People could call us, write to us; they could suggest ideas and then we would meet with them. That’s how we engaged our collaborators, for example, Artūras Raila.

N. U. At that time, his polemic and provocative work Girl is Innocent came out, so we collaborated with him on an episode of Artist and Education.

G. U. Through an open call we met with poets Algimantas Lyva and Robertas Kundrotas. They suggested a performative walk in the Rasos Cemetery where they would address the prominent personalities resting there and discuss co-existence and collaboration. At the time, Algimantas and Robertas had earned the titles of the worst Lithuanian poets. The walk with them was a blind date and live experiment. In addition, Kundrotas was also known as the best expert of an underground music. tvvv.plotas became a space for such experimental meetings, where various unconventional ideas were tested and unexpected encounters took place. Part of the video material was gathered in 1998, when we travelled around Belgium and the Netherlands. That year, the second Manifesta biennial took place in Luxembourg with a breakthrough participation from Deimantas Narkevičius. We visited that Manifesta, talked to the artist, his brother, and the curators there. Later, we drove around the harbors and suburbs of Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Rotterdam, visiting squats and other informal initiatives. The circle of our interlocutors ranged from Marie-Jo Lafontaine, whose main worry was to raise two million dollars for her exhibition in the Guggenheim Museum, to underground artists, who were forced to sell heroine to afford the equipment needed to create media art. We were highly interested in observing the emergence of new media institutions such as V2 in Rotterdam and de WAAG in Amsterdam, in meeting with and talking to such curators and theoreticians of new media as Andreas Broeckmann, or Geert Lovink. At that time, we needed visas to travel. It was really expensive; we had to sleep in our tiny car. Yet those journeys were really formative, and our camcorder became our visual diary. Though only a small portion of that material was used for tvvv.plotas, we learned a lot from those trips, encounters, and conversations.

J. B. What impact did local and global video art practices have on the aesthetics of your television program and on the general logic of its construction? Did this affect you in any way when working on the program? Did you have the ambition of turning this project into an artwork?

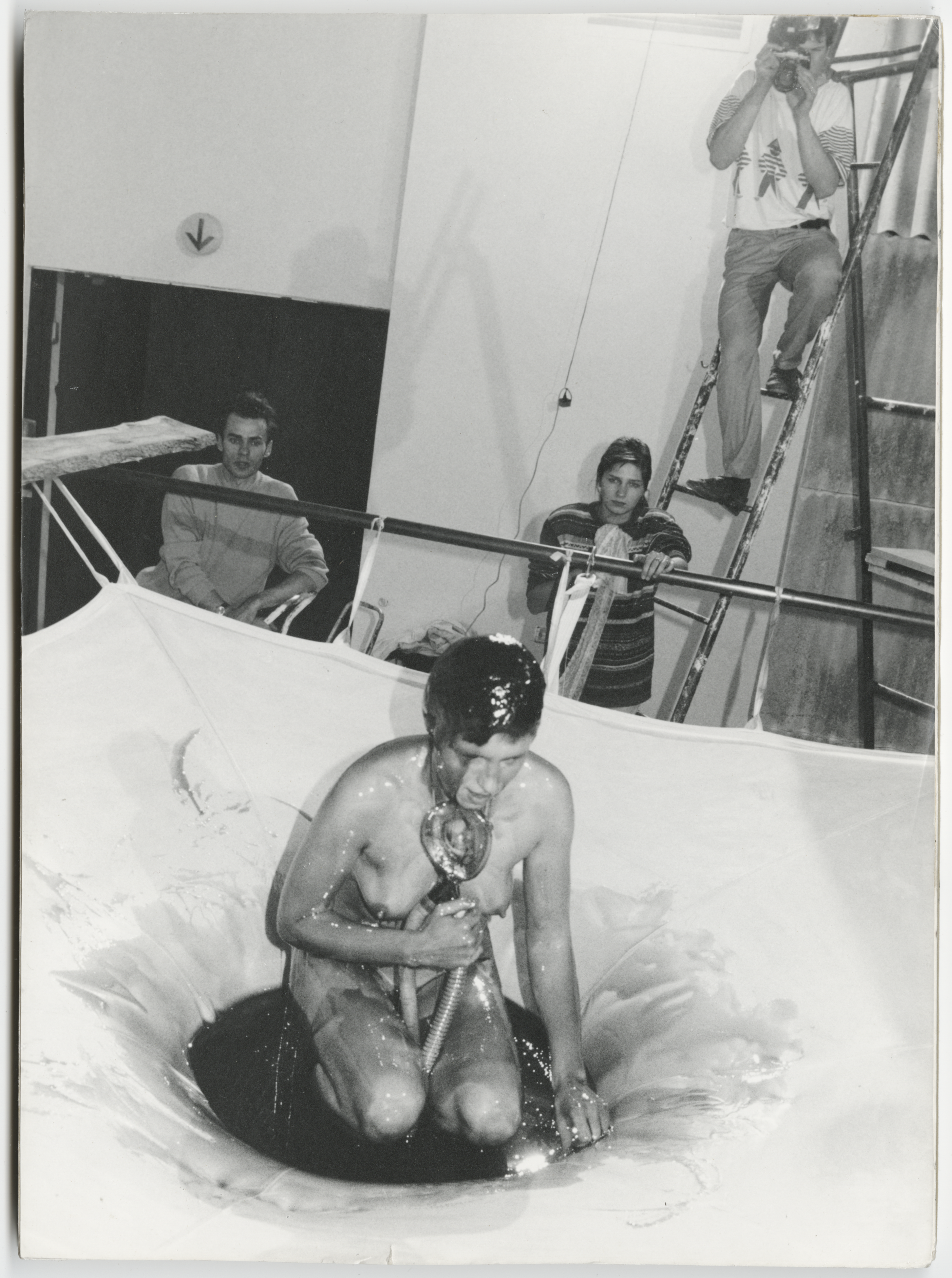

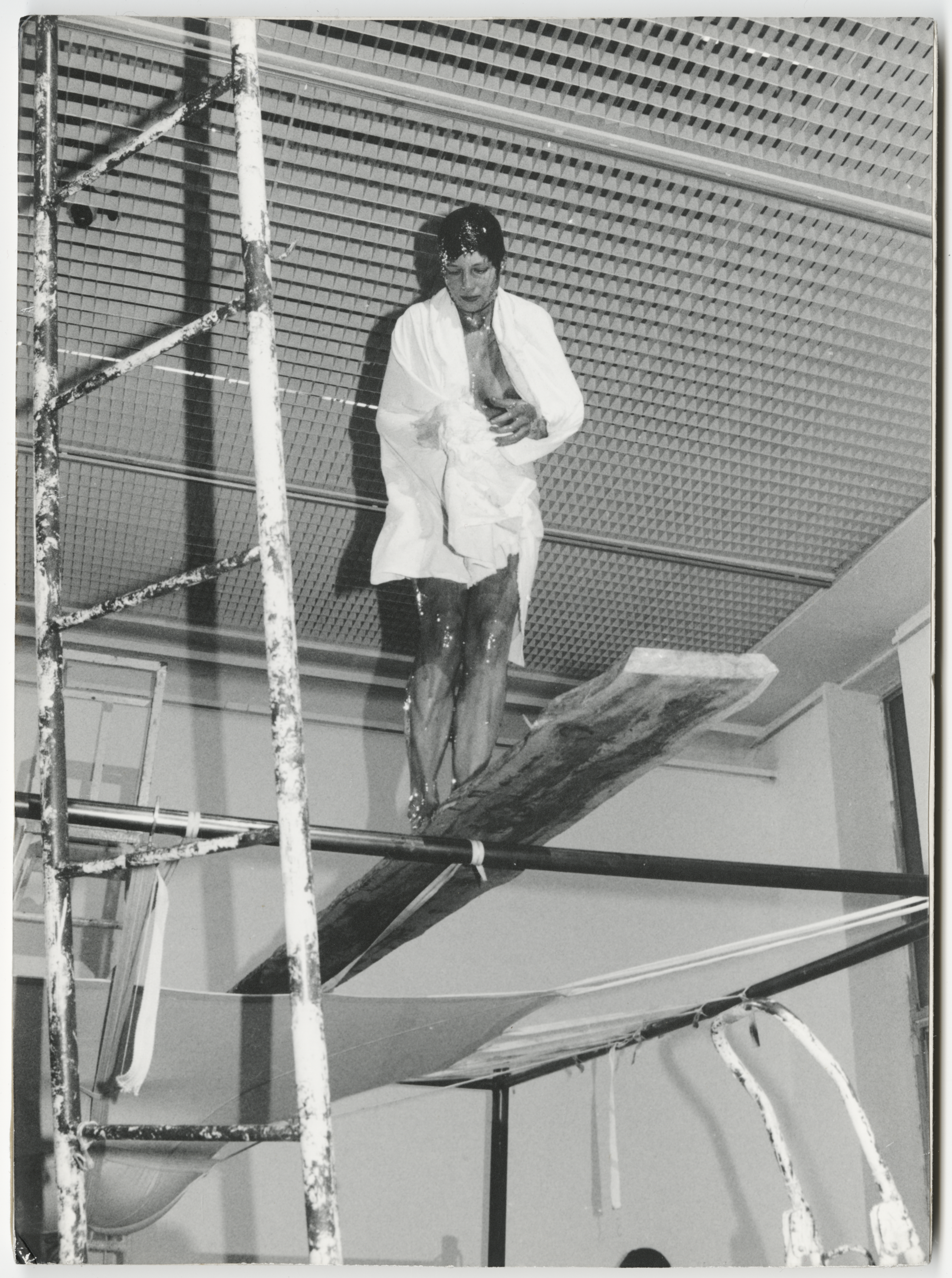

G. U. Of course, the cinematic turn made an impact for the whole generation of the 1990s. The shift toward the narrative constructed in cinematic language and space served as a breaking point in visuality, leaving beyond the restrictive boundaries of painting or sculpture and opening up the possibilities for multimedia narration, nonlinear time editing, and experiments in combining text, sound, and image. The Lithuanian art scene registered this change with Deimantas Narkevičius transitioning from sculpture to cinematic narrative and Eglė Rakauskaitė and Gintaras Makarevičius shifting from painting to video performances, for example.We observed how Douglas Gordon, Isaac Julien, Steve McQueen, Stan Douglas, and other artists engaged the phenomenon of video installation. In Lithuania, that zeitgeist was captured in the exhibition Twilight, when the entire CAC was plunged into darkness and turned into a black cube6. Within this context, we wanted to try out a different orbit and approach things from a different perspective. Thus, instead of a video work, we positioned the television program as a thought form.

N. U. To our understanding, the regular art scene was lacking a certain social engagement, a networked aspect that became characteristic of the practice we later developed. Thus, in tvvv.plotas, we probed that social engagement aspect, combining media art and migrating cinematic forms. G. U. Rather than video art, the new media art was more inspiring for us. With media departments proliferated by the art schools in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Scandinavian countries in the 1970s and 1980s, there had already been several generations of active practitioners and theoreticians shaping discourse through media art events and festivals. We traveled to meet people and engage in workshops at the Next 5 Minutes in Holland, ISEA, Ars Electronica, Transmediale. That was the world shaping its promise in parallel to the regular art scene.

J. B. But can that very fact that you treated video and its construction in a relatively liberal way, and it was really dense, diverse in tvvv.plotas and played a very important role, be regarded as an argument that your program was actually flirting with the forms of video art?

G. U. Absolutely. If we had come from the world of journalism or advertising or television studies, the situation would have been completely different. But since we had come from the sphere of visual arts, our universe had been shaped by different visual experiences and sensibilities. Here conceptual, critical practices, performativity, and, ultimately, sound and theater, and even avisuality (things beyond the visual), encouraged by the avant-garde, were considered.

N. U. Yes, such an eclectic aesthetic experience informed our critical reflection. Image structure, montage, and editing reflected the video experiments we were encountering and studying.

G. U. The exhibitions Ars 95 Helsinki and documenta X of the 1990s, with their sections dedicated to new media and internet art (presented offline), had a really great impact on us. Witnessing new communication experiments, we were pondering how to bring this new language unfolding in front of us into television space. And that is exactly what we were trying to do with the webcasts and online chat rooms.The NowHere exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art made a great impression on us in 1996. We spent an entire week there.

N. U. That was the most sophisticated exhibition that had a truly formative effect on us.

G. U. NowHere mixed rave culture with psychedelics vis-à-vis the most recent technologies, the internet. The early spatial performance work of Vito Acconci, the editing concept of Harun Farocki, the systems aesthetics of Hans Haacke, the punk video of Pipilotti Rist, the design fiction of Jane and Louise Wilson, the archival turn of Johan Grimonprez, this all we found resonant. Perhaps the breaking point was Hybrid WorkSpace, the online art project curated by Geert Lovink for the documenta X in 1997. It seemed to be more radical than video art at the time. Our radars were tuned toward the specific genealogy of cybernetics, for example, tracing the pages of Radical Software, an experimental magazine of the 1970s that combined ecology and media, and brought out such artists as Frank Gillette or Paul Ryan, who experimented with video streaming technologies back in 1960s and to whom video art served as an alternative form of cultural communication.

J. B. Was tvvv.plotas presented as an artwork in any exhibitions?

G. U. Yes, it was, several times. For example, at the exhibition in BAK (Utrecht) in 1999, where tvvv.plotas was staged as an interactive video installation projected on-screen and supported with a computer running software. Programmed with Macromedia Director, the tiny scenes featured in all ten episodes where reshuffled to create new branching narratives. We didn’t have a laptop then, thus we had to carry a large desktop computer on the flight to Utrecht in 1999. The metal box tied with ropes irritated the airport officials in Schiphol Amsterdam, however, they allowed us to take it onboard as carry-on luggage.

N. U. We were learning media art by doing, thus we had to look for talents to help us implement the digital version of tvvv.plotas for the installation. We approached the web designers of Gaumina7 — who subsequently became our friends — for help. With them, we developed the website for the Transaction project, featured as part of larger installation at documenta 11 and Manifesta 4, and which in its own right became quite a landmark in interactive design. Building on the archive of short episodes together with the IT specialist Saulius Švirmickas, we developed a complex installation for the exhibition in Bristol. Our collaboration with Saulius on various projects continues to this day.

G. U. In 2000, we were invited to an exhibition at Arnolfini, Bristol’s international center for contemporary arts. We came up with quite a challenging plan, which from a technological perspective was truly ambitious and we are still surprised by it today. Conceived as a spatial installation, it invited the public not only to watch the scenes and follow the narratives but also to construct their own pathway through the archive by selecting specific topics and themes from the ten episodes. While viewers were browsing the video archive, “the plotas system” was printing the transcripts of the watched episodes. The record of their browsing was building new stories rendered by the machine and printed in styles and typefaces corresponding to the video scenes. That was yet another iteration, another layer of a spatial narrative embodying a subjective experience of the archive. The installation was mentioned in a review in The Independent that stated: “How great Lithuanian Television is. The BBC should definitely learn from it.”Another iteration of the tvvv.plotas installation was featured at the exhibition Are You Ready for TV? curated by Chus Martínez at MACBA, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona, in 2010. This exhibition focused on the encounter of art and television, where TV shows created by various artists were discussed not only as pictorial strategies but also as experiments in the production of public space. The exhibition that traveled to other museums in Spain brought together works from the period of 1960-2010, and presented such artists as Jef Cornelis Guy Debord, Harun Farocki, Alexander Kluge, Martha Rosler, and Andy Warhol, among others. Alongside the strategies by artists infiltrating television was a collection of diverse television programs on art as well as reflections on television by philosophers. The exhibition proposed contemporary art as “a means for television to transcend the looming obsolescence of news and conquer small patches of the future.”8

J. B. Would you agree with the statement that television was the most effective (contemporary) art presentation platform at the time? How do you see the situation now? In your opinion, what has taken over the role of representing audiovisual art today and in what forms is it performed?

G. U. One of the episodes in tvvv.plotas on Modernism and Contemporary Art captured comments from members of the delegation of Lithuanian artists and curators going for the first time to the Venice Biennale in 1999. It was either television or the bus itself that circulated the news from the art world, and the stories travelled by word of mouth. In addition to a small number of individuals traveling to international art events, the majority of the public only saw global art on television or in magazines.Today, magazines no longer play a role in disseminating the news. It has been a while since 2005, when criticism transitioned online. Even academia, which is built on peer review publications and books, contributed to this transition. When blogs and social networks became acknowledged and credible venues for academia, the transformation took place. Twitter and Instagram became legit platforms for artistic and curatorial research. Everything became more viral, including television itself moving online.

N. U. Today there are many channels and podcasts streamed via various platforms. These can actually shape a viewer (internet user) in ways that are hard to imagine.

G. U. It seems that technological inventions should guarantee democracy. However, paradoxically enough, the power structure of the art world was never reshuffled; it only reinforced its domination. Meanwhile, intellectual hierarchies regrouped. If some time ago, the magazines October or Parkett shaped the discourse and maintained the “level,” now it is Instagram that has a monopoly on affect previously owned by magazines and television.

1Jutempus Interdisciplinary Art Projects (better known as the project space Jutempus) was a public body established in 1994 by the artists Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas together with the art critic Saulius Grigoravičius and the sculptor Mindaugas Šnipas. It operated as a physical venue during 1993–1997.

2The project carried out by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas in 2000–2004, where the artists researched film archives and female roles in Lithuanian Soviet cinema, exploring the resistance to patriarchalism, the lack of women’s voices, and the grassroots of feminism.

3The project “Artist’s Portrait” by Raimundas Malašauskas, published in the fashion magazine Linija (1998), presented a series of photographs (by the photographer Audronė Vaupšienė), where the CAC curator was posing dressed in the cult clothing of other Lithuanian artists. “The name of an owner gives a nameless garment its value and price,” the curator commented.

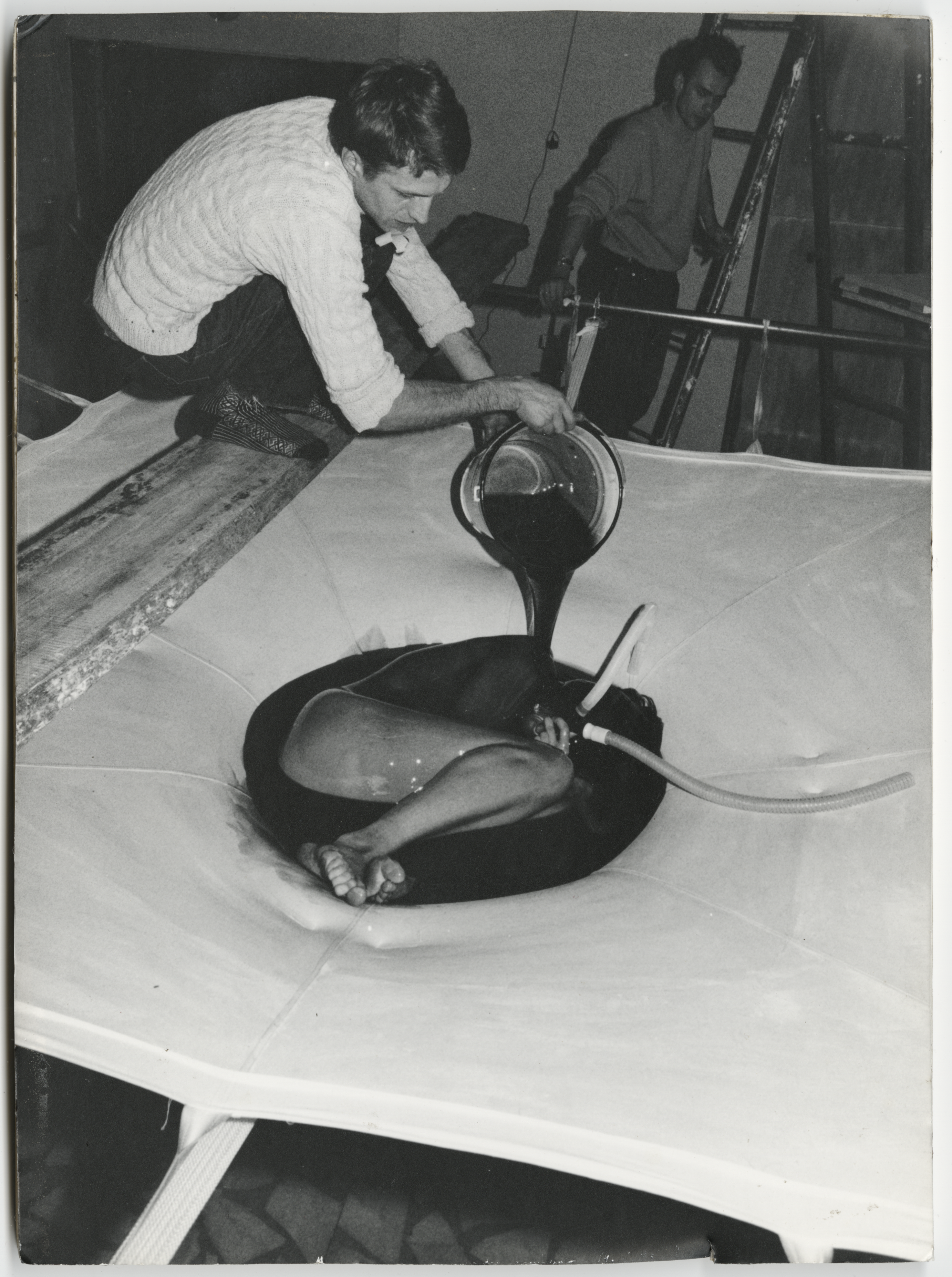

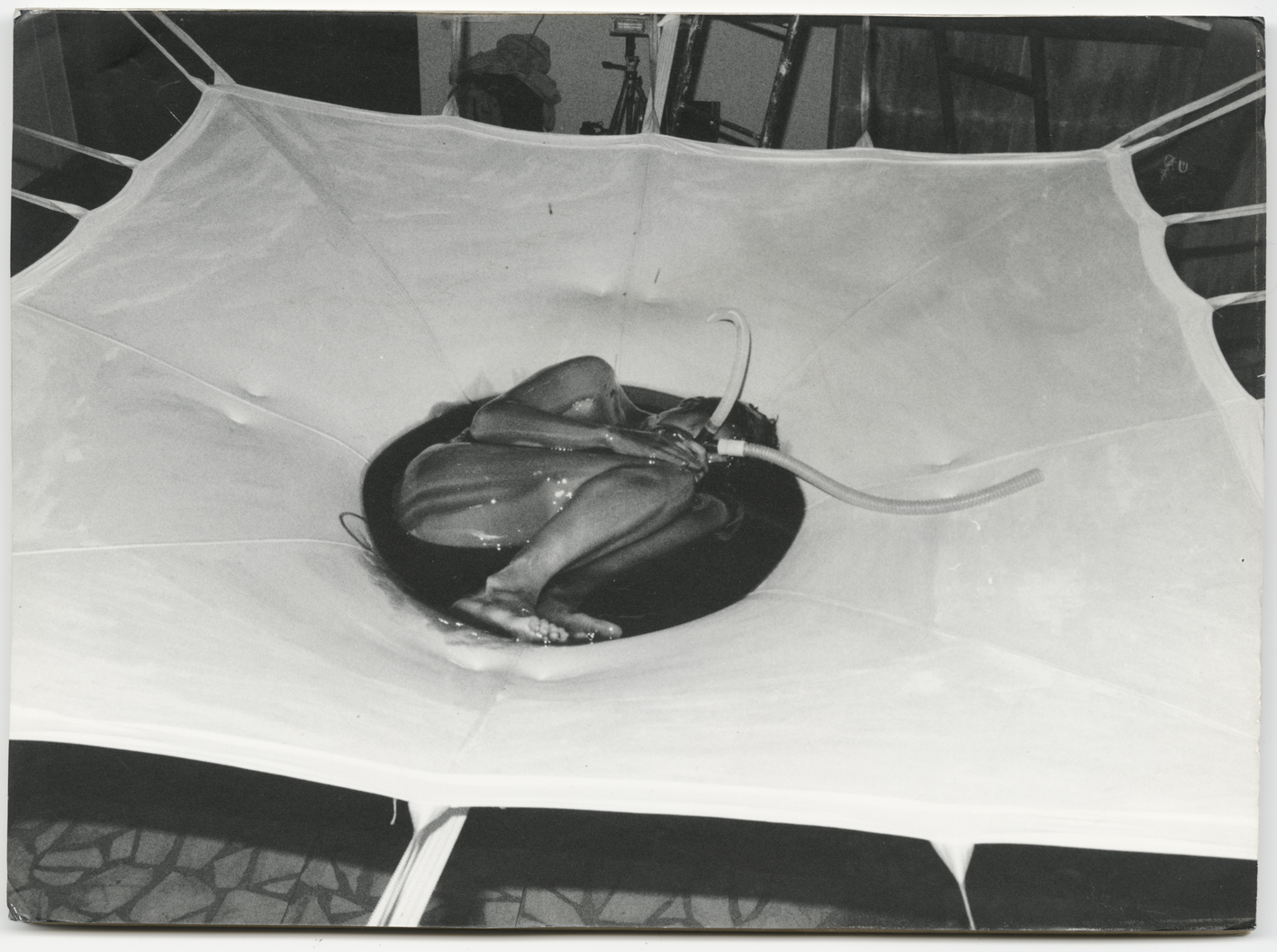

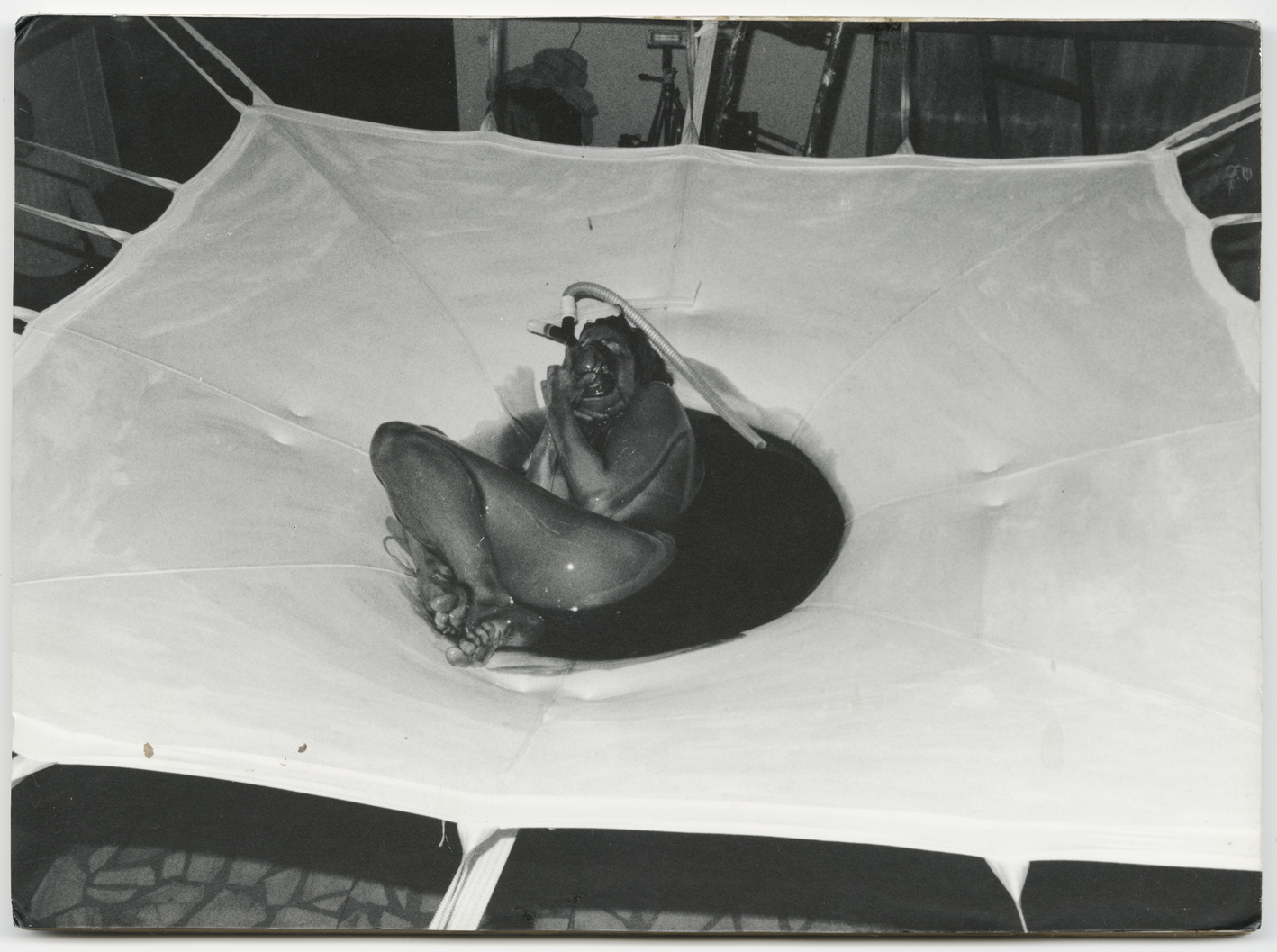

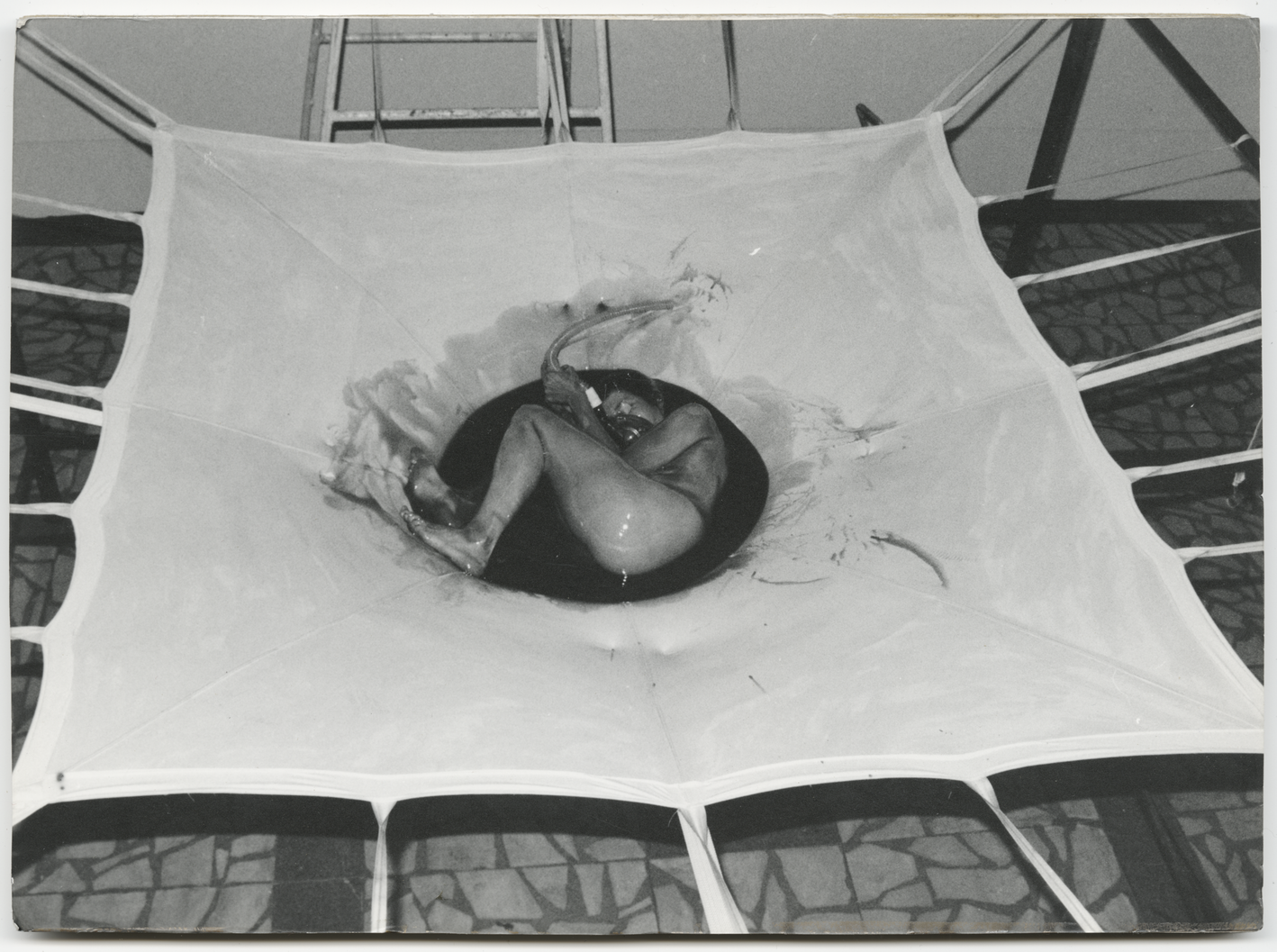

4In the period from February 17, 1999, to July 7, 1999, ten episodes were released under the following themes: “Artist and Communication,” “Artist and Education,” “Artist and Institution,” “Artist and Collaboration,” “Artist and Children,” “Artist and Relatives,” “Artist and Sound,” “Artist and Statement,” “Artist and Modernism/Contemporary Art,” and “Artist and Body.”

5Betacam is a professional analog video recording format recorded on a half-inch oxide-formulated cassette tape.

6The fifth Soros CAC Lithuania annual exhibition displayed at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius in 1998. The exhibition presented the projects based on the media technologies available at that time.

7Gaumina, UAB is the largest internet solutions company in the Baltic states that started its activities in 1998.

8Enrico Ghezzi, film critic.